Better batteries through biology

Could provide two to three times greater energy density --- the

amount of energy that can be stored for a given weight --- than today’s

best lithium-ion batteries

November 15, 2013

[+]

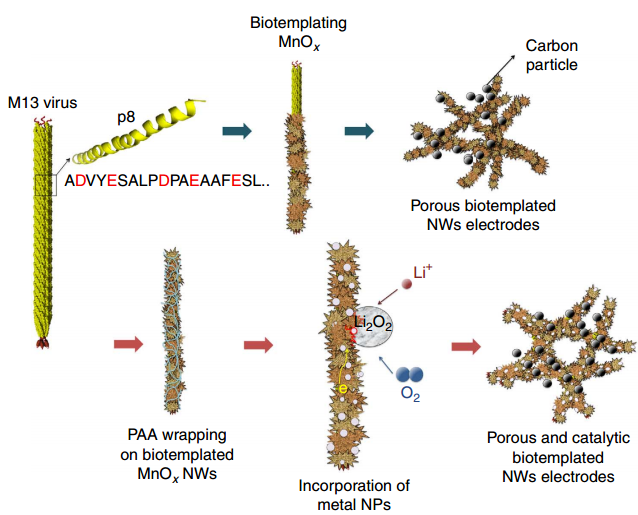

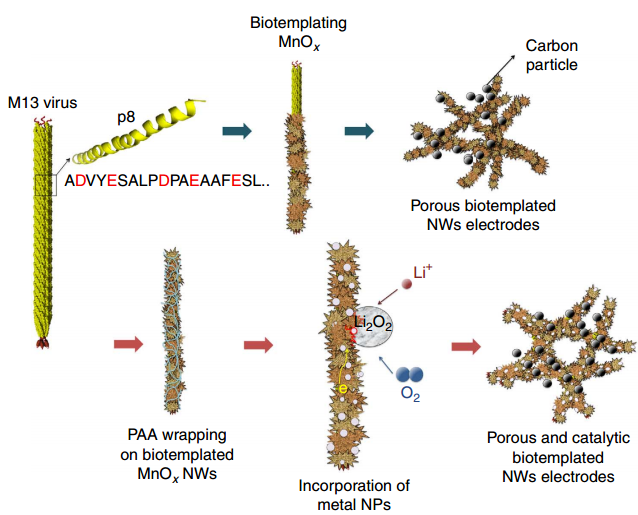

MIT researchers have found that

adding genetically modified viruses to the production of nanowires,

which can serve as one of a battery’s electrodes, could help solve some

of the problems in creating lithium-air batteries.

(Credit: Dahyun Oh et al./MIT)

These batteries hold the promise of drastically increasing power per battery weight, which could lead, for example, to electric cars with a much greater driving range. But bringing that promise to reality has faced a number of challenges, including the need to develop better, more durable materials for the batteries’ electrodes and improving the number of charging-discharging cycles the batteries can withstand.

The new work is described in a paper published in the journal Nature Communications, co-authored by graduate student Dahyun Oh, professors Angela Belcher and Yang Shao-Horn, and three others.

More surface area, improved catalyst

[+]

The key is to increase the surface area of the wire, thus increasing

the area where electrochemical activity takes place during charging or

discharging of the battery.

Schematic

of a nanocomposite structure. Synthesis step of the metal

nanoparticle/M13 virus-templated manganese oxide nanowires (bio MO

nanowires) and the operational reaction inside Li-O2 battery cells

(credit: Dahyun Oh et al., Nature Communications)

The researchers produced an array of nanowires, each about 80 nanometers across, using a genetically modified virus called M13, which can capture molecules of metals from water and bind them into structural shapes.

In this case, wires of manganese oxide — a “favorite material” for a lithium-air battery’s cathode, Belcher says — were actually made by the viruses. But unlike wires “grown” through conventional chemical methods, these virus-built nanowires have a rough, spiky surface, which dramatically increases their surface area.

Belcher, the W.M. Keck Professor of Energy and a member of MIT’s Koch Institute for Integrative Cancer Research, explains that this process of biosynthesis is “really similar to how an abalone grows its shell” — in that case, by collecting calcium from seawater and depositing it into a solid, linked structure.

The increase in surface area produced by this method can provide “a big advantage,” Belcher says, in lithium-air batteries’ rate of charging and discharging. But the process also has other potential advantages, she says: Unlike conventional fabrication methods, which involve energy-intensive high temperatures and hazardous chemicals, this process can be carried out at room temperature using a water-based process.

Also, rather than isolated wires, the viruses naturally produce a three-dimensional structure of cross-linked wires, which provides greater stability for an electrode.

A final part of the process is the addition of a small amount of a metal, such as palladium, which greatly increases the electrical conductivity of the nanowires and allows them to catalyze reactions that take place during charging and discharging. Other groups have tried to produce such batteries using pure or highly concentrated metals as the electrodes, but the new process drastically lowers how much of the expensive material is needed.

Up to three times greater energy density

Altogether, these modifications have the potential to produce a battery that could provide two to three times greater energy density — the amount of energy that can be stored for a given weight — than today’s best lithium-ion batteries, a closely related technology that is today’s top contender, the researchers say.

Belcher emphasizes that this is early-stage research, and much more work is needed to produce a lithium-air battery that’s viable for commercial production. This work only looked at the production of one component, the cathode; other essential parts, including the electrolyte — the ion conductor that lithium ions traverse from one of the battery’s electrodes to the other — require further research to find reliable, durable materials. Also, while this material was successfully tested through 50 cycles of charging and discharging, for practical use a battery must be capable of withstanding thousands of these cycles.

The work was supported by the U.S. Army Research Office and the National Science Foundation.

Abstract of Nature Communications paper

Lithium-oxygen batteries have a great potential to enhance the gravimetric energy density of fully packaged batteries by two to three times that of lithium ion cells. Recent studies have focused on finding stable electrolytes to address poor cycling capability and improve practical limitations of current lithium-oxygen batteries. In this study, the catalyst electrode, where discharge products are deposited and decomposed, was investigated as it has a critical role in the operation of rechargeable lithium-oxygen batteries. Here we report the electrode design principle to improve specific capacity and cycling performance of lithium-oxygen batteries by utilizing high-efficiency nanocatalysts assembled by M13 virus with earth-abundant elements such as manganese oxides. By incorporating only 3–5 wt% of palladium nanoparticles in the electrode, this hybrid nanocatalyst achieves 13,350 mAh g−1c (7,340 mAh g−1c+catalyst) of specific capacity at 0.4 A g−1c and a stable cycle life up to 50 cycles (4,000 mAh g−1c, 400 mAh g−1c+catalyst) at 1 A g−1c.

(¯`*• Global Source and/or more resources at http://goo.gl/zvSV7 │ www.Future-Observatory.blogspot.com and on LinkeIn Group's "Becoming Aware of the Futures" at http://goo.gl/8qKBbK │ @SciCzar │ Point of Contact: www.linkedin.com/in/AndresAgostini

Washington

Washington